- Home

- Perez, Rosie

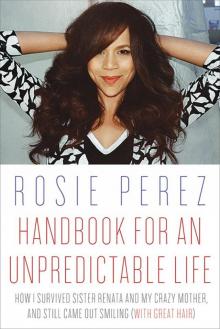

Handbook for an Unpredictable Life: How I Survived Sister Renata and My Crazy Mother, and Still Came Out Smiling (with Great Hair)

Handbook for an Unpredictable Life: How I Survived Sister Renata and My Crazy Mother, and Still Came Out Smiling (with Great Hair) Read online

Copyright © 2014 by Rosie Perez

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Archetype, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN ARCHETYPE with colophon is a trademark of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perez, Rosie.

Handbook for an unpredictable life : how I survived Sister Renata and my crazy mother, and still came out smiling (with great hair) / Rosie Perez. —First edition.

1. Perez, Rosie, 2. Actors—United States—Biography. 3. Choreographers—United States—Biography. I. Title.

PN2287.P387A3 2013

791.4302′8092—dc23

2013033958

ISBN 978-0-307-95239-4

eBook ISBN 978-0-307-95241-7

Jacket design by Michael Nagin

Jacket photographs: Eric Johnson

All photographs are courtesy of the author unless otherwise credited.

v3.1

Dedicated to

Tia

Dad

All the kids from the Home

And … My Mother

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Preface

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Photo Insert

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Acknowledgments

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This book is based on my recollection of what went down and what was told to me by friends and family. Some names, characters, and situations have been changed to protect the innocent and the guilty. I hope you enjoy …

PREFACE

“The artist is born in the suffering child.”

I SAW Israel Horovitz, the playwright, say this in the documentary I Knew It Was You: Rediscovering John Cazale, a celebration of the short career of the actor who played Fredo in The Godfather. I was moved by this comment, but angered too, because more often than not that cliché is all too true, and one thing I will not be defined by is a cliché.

I didn’t really want to write about this story of mine. Yet I felt like I was supposed to write it, like it was a responsibility that I couldn’t avoid. It’s so hard to go there, you know? And I was always concerned that if and when I did tell my story, I would have to constantly defend my recollection of my truth. Unfortunately, I have family relations and folks who “knew me when” who, solely out of motives of fame, greed, or both, have jumped out of the woodwork to contest my truth and would do it again, which would only waste time and miss the point. And more important, I was concerned that people would pity me, and I don’t want anyone’s pity. That is not the point either. The point is to get it out, to validate my feelings, to communicate how good it feels to no longer live in fear of what others may think, and to share my journey and move on. I have survived. And in writing my experiences I know that however sad it was, it is more or less the same story shared by a lot of people who are messed up as a result of a difficult childhood.

The abuse and neglect from my mother and the time I was forced to spend in Saint Joseph’s Catholic Home for Children, aka “the Home,” have affected a big part of my life. And I’ve hated that fact. I’m a forward-moving and positive-thinking person, and it was hard to have that albatross hanging around my neck. I’ve hated my past so much that I’ve spent countless hours downplaying or even hiding bits of the truth of my childhood in an attempt to make it seem less severe, less hurtful, less shameful, than it felt.

I hated the fact that my mother was crazy. I wanted her to be normal. Even when she acted normal—something that many mentally ill people can do, despite what you see in the movies—I was always walking on eggshells, waiting for the insanity to hit. And when it hit, it hit hard and fast—leaving deep emotional and physical scars.

People who are “normal” as a result of good parenting—even just decent parenting—are very lucky. Yeah, I know, everyone’s hell is relative, and blah, blah, blah, but those people are very fortunate. Am I bitter? No, not at all. Every child should have a loving and stable upbringing. There would be less violence and hate, for sure. But most of us didn’t, and regardless of what the experts say, trying to get past your past sucks. Most of us would rather just ignore it or numb it with any or all types of drugs, legal or illegal. Those of us who are a bit stronger—and I say that without judgment—try to avoid those options and deal with our past legitimately: through psychoanalysis, psychiatry, medications, spirituality, whatever. Truth be told, even when you work every day to do so, it’s hard to not lose it, or give up, or worse, fall into a depression.

That’s the worst—depression. I’m a relatively happy person who also happened to be clinically depressed for years (sorry, that just cracks me up). I know that it’s probably hard for most people, especially those who know and love me, to fathom that, because I’m a person who’s usually in a good mood, cracking jokes or telling funny stories. And the good moods are absolutely, 100 percent authentic. It’s just that there was this underlying feeling of blah, or sadness, or even fright, which at times I was aware of and at other times I was not. I refused to let this hold me down. I wanted to move on. I wanted to fully enjoy the wonderful life I’ve worked so hard to obtain.

I finally resorted to seeking professional help, the one thing I had resisted for years. When my shrink diagnosed me with dysthymia—a sneaky, chronic type of depression—I was actually relieved. God bless America two times for that, as my Tia Ana would say. It’s most common with people who suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Yeah, I had that one too. Still do. But now at least I had a starting place and could take some kind of ownership of the healing process.

After a couple of years of therapy, and I don’t know exactly when or how it happened, I noticed that my depression wasn’t there and the PTSD subsided considerably. I felt joyful, secure, and empowered. My inner strength and sense of self had never been stronger. I guess I allowed time to play its role, and I did my part by working hard on myself to grow past the pain. Gosh, I sound so full of shit there. Let me be more honest: I grew past most of the pain and continue to do the work. Every day gets better. xo

—Rosie Perez

June 2013

CHAPTER 1

THEY MET in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Although Ismael was married to his wife, Halo, at the time, he was on his way to his sister’s, my Tia Ana’s house, to meet her girlfriend for a date. Yes, folks, a date. And my aunt cosigned. He was the quintessential Latin male when it came t

o women and romance, minus the machismo. It wasn’t clear if the date knew that Ismael was married or not. He never really kept it a secret, but then again, he wasn’t the first to volunteer that information either—you know what I’m saying? It probably didn’t matter—the man had mad game. Ismael wasn’t gorgeous, but he was what people would call brutal-sexy, meaning not conventionally good-looking, but extremely attractive and charismatic. He could be very suave too, in an intentionally goofy way. He had this undeniable, unassuming, yet aggressive charm that would knock the most beautiful women off their feet.

Ismael had been a merchant marine during World War II, and in the Korean War after that, though he never wanted to talk about it. He hated war, but loved America, and he loved to wear his army jacket whenever he was not on a date. He always dressed sharp for his dates—he had mad style. After the wars were over, he spent half of his time out at sea, the other half in Puerto Rico with his wife, and whatever free time he had left in New York visiting Tia, but mainly living the life of a playboy.

Tia’s full name was Ana Dominga Otero Serrano-Roque, God rest her soul. Her friends called her Minguita, which came from her middle name, Dominga. Her style was simple and pragmatic, but not in an old maid type of way. And she always wore dresses. I saw her in a pair of pants for the first time when I was in my twenties, and I was shocked. She’d gotten fat after having four kids—three girls and one boy—all of whom she had to give to the oldest of her two brothers, Monserrate, to raise because she had a nervous breakdown and was sent to “the Loony Bin” (that’s where they sent women back then when they got hysterical) when she caught her husband in bed with her girlfriend—scandalous! When she got out of the “hospital,” her brother, Tio Monserrate, only gave her the girls back. He kept the boy—we’ll get into that later. This left a pain in her heart that never healed.

Tia lived on the corner of Wallabout and Lee Avenue in a shotgun-railroad apartment in a broken-down tenement building. It was at the edge of the Hasidic Jewish neighborhood of South Williamsburg, an area that looked as if time had stopped in the 1940s. The Hasidic Jews walked around dressed in the style of that period, all year round. To this day, the neighborhood is still 90 percent Hasidic and retains the same vibe. Tia lived there with her three daughters, Titi (whose real name was Carmen), Millie, and Cookie (whose real name was Lourdes, pronounced Lou-day); little Lorraine would come later. Across the hall were her friends, also all Puerto Rican. When I was little, I used to think the whole building was Puerto Rican, but in fact it was just those two apartments.

The place was sparsely decorated, but it featured a few of the stereotypical tacky Puerto Rican items: a plastic-covered sofa; fake eighteenth-century porcelain figurines that sat on a wooden television/bookshelf, and lastly, the staple of all Nuyorican interiors, an oil rug painting of The Last Supper hanging over the plastic-encased sofa. The French doors that led into her bedroom, just off the living room, were my favorite feature of Tia’s house. The rest of the place was furnished with eclectic stuff that people left out on the curbside for the garbage trucks in expensive neighborhoods.

• • •

The air was brisk that December afternoon. As usual, Ismael was dressed sharp for his date and had the look of a well-manicured man: suit and tie, of course, with a gray overcoat and scarf, and a fly hat to finish it off. He loved hats. He liked his women to dress up as well. If a chick wasn’t that pretty—though he usually only hooked up with the fine-looking ones—but she knew how to dress and carry herself, he was there, on the hunt.

Tia’s girlfriend, the one she was setting her brother up with, was fairly attractive and well groomed, despite her lack of money. (It can happen, folks—there are poor people who can pull it together. We don’t all look busted like they show us in the movies.) She waited anxiously for her date to arrive, pacing back and forth for an hour, constantly looking out the window to see if he was coming down the block.

Before he arrived, this girl’s sister, Lydia, stopped by, along with a couple of other young ladies, to sneak a peek at this man her older sister had bragged about for a week. Lydia, in her early twenties at the time, had been married since the age of fourteen and had five children. She was also stunningly beautiful, eclipsing all of her sisters by a mile. She was a sexy siren, cunning, self-centered, condescending, mean at times, and extremely intelligent. She was a cross between the movie stars Ava Gardner and Miriam Colon, with a petite, apple-shaped face and a wry smirk.

Lydia had been a singer in Puerto Rico until her husband, ten years her senior, made her quit, crushed all her dreams, and moved her to New York City in the fifties. Although she was madly in love with her husband, she feared him. He used to beat the shit out of her because of her mouth. Her tongue was cutting—sharp and deadly. She would never back down from a confrontation. And since she was mentally ill, she never stopped mouthing off, so he never stopped beating her.

Lydia felt trapped as a poor housewife and young mother of five. Her spirit was way too free and wild for that kind of life. She hated her husband’s control over her, but was torn between feelings of resentment and intense love, a powerful combination, especially for someone suffering from an undiagnosed psychological disorder. So she did what most paranoid schizophrenics would do with that kind of anger: beat the shit out of her kids. (I know—horrible, but sadly all too true.)

So, as Ismael strolled down Wallabout Street, Lydia’s older sister stuck her head out the window, then quickly tucked it back inside, screaming with glee. While she was fretting about fixing her makeup, Lydia quietly went over to the window to see him for herself.

Just at that moment, my father looked up and took in Lydia’s mesmerizing beauty—that’s how he described it to me anyway—and stopped dead in his tracks. Lydia gave him one of her infamous smirks and casually popped her head back inside. With a nonchalant shrug of her shoulders, she turned to her sister and said, “He’s all right looking—a little ugly. Ay, fo, the garbage is so stinky. I’m going to take it out for you, Minguita. I’ll be right back.”

She grabbed her coat and quickly ran down the staircase. Ismael ran up just as fast. When she saw him come into view, she slowed down to a sultry strut, step by step.

“When I saw your mother, I almost had a heart attack right there on the stairs,” my father told me years later. “I had to grab my heart. I couldn’t breathe.” (I know, Puerto Ricans, melodrama—gotta love it.)

They met halfway on the staircase, stopped, and just stared at each other without saying a word.

“You are the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen in my life. Would you do me the honor and join me for a cup of coffee?” he said, with a tip of his hat and a flirtatious smile.

She took his arm. Just like that, without a word to anyone, they took off. I don’t know what my Tia Ana or Lydia’s sister, the abandoned date, thought happened, but I know her sister was pissed when she eventually figured shit out.

Both of my parents were very sexual, so I’m sure they didn’t waste any time and probably had sex right away. That’s so embarrassing to say, on one level, and incredibly cool on another. It had to be pure lust, with a touch of whimsical romance—at least for my father it was like that. (With that scene on the staircase? Come on!)

I know it’s weird, but I’ve always wondered how it went down. Where did they go to do it? How did the room look? Was the bedding nice? Was it cold inside or was the radiator steaming heat? I imagine that everything was white—the walls, the sheets, and the curtains billowing from the slight crack of the window to let some air in because everything was crazy. (I was going to say “hot and heavy” but didn’t want you to think I’m a pervert.)

What about her, what about my mother? Was it romantic, or just an escape for her, or both? What was she wearing? My father never told me that. I even wonder if she had nice underwear on. I’m such a Virgo that I wonder if she looked put together, if she’d planned a nice bra-and-panties combination.

More important, I always wonde

red how she felt. Was she scared, even just a bit? I wonder if she thought of her husband as she and Ismael kissed, if she thought of her five kids as she started to undress. Did she give a shit about the consequences? Did she think, What the hell am I doing? Probably not. With the whole mental thing, and her self-centeredness, I’m sure she was just living in the moment. She sure didn’t give two shits about her sister whose date she stole.

Or perhaps she was just so disappointed in her life that she saw in Ismael a shot at escape—maybe for a moment, or maybe permanently. And she took it, regardless of who got hurt along the way. I do know this about my mother: she always wanted more than she had. And not just with money, but with life. It’s kind of sad, it really is.

• • •

Within months of their meeting, she got pregnant with me, left her husband when she started to show, took her five kids, and moved into an apartment in Bushwick, Brooklyn, that my father set up for her. He then left his wife and moved in with them—real classy move on both parts, right? He took her on hook, line, and sinker. It was a scandal of large proportions.

It was great the first few months. My half-siblings loved my father. He was a captain’s chef on the ships and could cook his ass off; he helped with the cleaning and played and talked with them like they mattered. They thought they had a new beginning, had seen the light at the end of the tunnel. Then the shit hit the fan. As the months passed and my mother’s pregnancy progressed, Ismael slowly started to see her mental malady. He didn’t understand at first—the unprovoked violent outbursts, the combativeness that would drag on for hours. He was at a loss. He tried to please her, but nothing worked. By the eighth month of her pregnancy, she was going at him full tilt—rages, paranoia. The arguing was constant, and the suspicion was at an all-time high. About that, I can’t blame my mother. With his reputation as a womanizer, and considering the way they started off, well, it’s understandable that anyone, even a crazy person, would assume the worst.

Handbook for an Unpredictable Life: How I Survived Sister Renata and My Crazy Mother, and Still Came Out Smiling (with Great Hair)

Handbook for an Unpredictable Life: How I Survived Sister Renata and My Crazy Mother, and Still Came Out Smiling (with Great Hair)