- Home

- Perez, Rosie

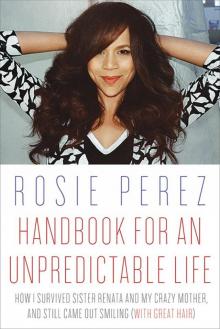

Handbook for an Unpredictable Life: How I Survived Sister Renata and My Crazy Mother, and Still Came Out Smiling (with Great Hair) Page 2

Handbook for an Unpredictable Life: How I Survived Sister Renata and My Crazy Mother, and Still Came Out Smiling (with Great Hair) Read online

Page 2

What’s sad, and ironic, is that my father told me he was being faithful. Lydia was his world, and he loved her children. But Mom couldn’t buy it. That paranoia was too strong.

One day he came home and she started in.

“Where the fuck was you? Out fucking some fucking slut?” my mother screamed. She had a mouth like a truck driver. (Explains a lot, right?)

He pleaded and pleaded until he finally snapped and started to scream back, told her he was sick of her craziness, that he was leaving her. So, of course, she got her pistol. (Yes, Mom carried a pistol.)

“You gonna leave me? Me? You motherfucker!” she yelled.

Bang! Bang! Bang!

She started shooting. My father jumped out the window, climbed down the fire escape—while she was still shooting—and ran for his life. He never went back.

This was my father’s recollection of events.

Now, in fairness to Mom, her version of this story is that they’d had an argument over his cheating—at least they agreed on that—and that he started screaming, she started screaming back, and then he packed his things and left her, eight months pregnant with me, and her five kids. However, according to her, there was no gun, no shots fired. I tend to believe Pops, since other people who lived on their block confirmed his story to me over the years. Plus, Mom did carry a pistol and was quick to pull it out. She would frequently bring it along with her, in a plastic bag for “protection,” just to go to the corner store that was half a block away—true story. Either way, it must have been tough to be left eight months pregnant.

Lydia, heartbroken, had no other recourse than to go back to her husband, Ventura, who everyone called Durin, with her tail between her legs. Ventura was a tall, dark, extremely handsome, smoldering-with-sex-appeal grump who had his moments of kindness. He was also a man of very few words. (I think I heard him speak maybe a total of three sentences the entire time I knew him—no kidding.) He took her back, but wasn’t happy about her being pregnant with another man’s baby, even though he claimed me as his and gave me his last name—all to preserve his and Lydia’s honor, of course. When she gave birth to me at Greenpoint Hospital, in September, there was a rumor that Ventura put a hit out on my father if he dared to show his face there.

Tia told me she stayed all day and through the night, standing guard, gazing at me through the maternity ward’s viewing window, falling deeply in love with me. A few mutual friends of Tia’s and my mother’s walked up, stood beside her, scanning the rows of newborns, searching for the scandalous love child.

“Hola, Minguita, which one is Lydia’s baby?” they asked.

“That one,” she replied, pointing to me.

“Which one?” they’d ask again, feigning confusion.

“That one, the tiny blonde, jellow one,” Tia answered again.

Shock crossed their faces. They were giddy and gasping.

“Oh!” one of them stated with an affected melodramatic pause. “Are you sure?”

“You know, Minguita,” another friend chimed in, “that baby kind of looks like … you … and your brother.”

Tia coyly shrugged her shoulders, trying hard to play along, concealing her pride in order to save the family’s face. She knew that they knew I was her brother’s notorious newborn, but she didn’t dare let on.

It didn’t matter. The streets of Bushwick were filled with even more bochinche (gossip) after that! All of Lydia’s other children were strapping like their father, had dark hair like their father, and had a reddish-olive complexion to boot. There I was, yellow, with sandy blonde hair and tiny as shit. I looked just like my father. There was no doubt that I was his.

Ismael snuck into the hospital late that night. When Tia saw him, she was pissed. She had told him that there was a hit out on him. But he said he didn’t care. Actually, he did. He just cared about me more. He told me later that he was scared as shit as he crept through the hospital’s hallways. He went up to the window, looked, knew who I was immediately, and cried, just cried. Then he ran out, without a word to his sister or anyone else. There was no shooting—just sad, pathetic drama.

• • •

Just a week after my birth Lydia decided to pay Tia a visit so she could see the baby. My mother arrived with me all bundled up.

“Hi, how are you? I brought the baby so you could see her,” my mom said in a panicked huff. “Listen, I have to go to the bodega. I’ll be right back.”

She handed me to Tia, left, and didn’t come back for three years. She never came to check on me. She never called.… And Tia never called her either. I guess the situation was understood and that was that.

CHAPTER 2

TIA SPOILED the shit out of me by smothering me with love and attention. Her three daughters—Titi, the oldest; Millie, the next oldest; then Cookie—were all instructed to take extra good care of me. When I was a baby, I thought they were all my sisters rather than my cousins, and they treated me in kind.

Everyone, all the neighbors also, treated me special, like a “miracle” baby. Some new friends thought that having another baby at Tia’s age was beyond incredible. Yes, a lot of people thought I was her daughter—to this day many are surprised to learn I’m not. Her dear friends knew the truth but never spoke on it. Tia never officially stated that I was not her daughter, but she didn’t explain the situation either. That was private family business. That’s why, when I was a baby, I knew her as my mother and referred to her as “Mommie” instead of “Tia.”

I was a good baby, happy, sweet, polite, and a ham, except when I had one of my crying fits. Apparently I’d have these screaming spells all through the night, and my cousin-sisters would take turns holding me and stroking me back to sleep so Tia could have her rest. I was probably screaming for my mother. By the time I was crawling, I’d sporadically start crying and banging my head repeatedly on the floor for no reason. Weird thing, I remember that. My cousin Millie later told me that every time I did that it would bring her to tears.

I remember a lot, as far back as one or two years old, mostly it comes to me in just bits and pieces, and flashes of images. Fortunately, I don’t just remember the bad things; I remember the good things too—especially the hammy parts! I loved television—from day one! And loved music even more. When I told Tia one day that I remembered dancing in my crib, her mouth dropped slightly and she said, “Ay, my goodness. You were less than one when you started doing that.”

The memory of dancing on my bed was really, like I said, just a flash of a moment. My cousin Millie filled in the rest. She said like clockwork, every day at three-thirty in the afternoon, I’d stand up in my crib, which was in Tia’s room, looking through the French doors into the living room, waiting for my cousins to come home from school. As soon as they came into view, I’d start gleefully jumping and screaming for them to put my favorite song, “I’m a Soul Man” by Sam and Dave, on the record player in the living room. And I wouldn’t stop screaming until they did.

As soon as the needle dropped, I’d hold on to the rail with one hand and do the “hitchhiker,” with my thumb sticking out, with my other hand. When I got tired, I’d suck on that thumb until I caught my breath and start hitching all over again—my cousins would die with laughter. Millie said that as soon as the record ended, I’d start screaming and they’d have to play it over and over until I was too exhausted to stand. She said at times I’d lie down in my crib from exhaustion, with my eyes closed, still dancing in my slumber.

What can I say, I was a cute kid, especially with my sandy blonde, curly, cotton-candy hair to boot … except for one major thing: I had the biggest forehead in all of Brooklyn. It was a monstrosity. Everyone would always tease me about it too. Everyone—except for Tia, of course—would call it a “big mofo,” which was short for “big motherfucking forehead.” What’s worse, when Tia would have a house party, she sometimes pulled all of my hair tightly back, up into a big moño (bun), leaving the rest of my hair to stick out like a wilted Afro puff on the t

op of my head—not a good look, people.

The house was always filled—with family, or neighbors, or just friends. It was like a revolving door. Tia was very social and generous. Parties were a constant: Spanish, soul, and pop music playing; people dancing; the smell of rice and beans and roasted pork—heaven. I remember it as a sea of legs and shoes. That’s probably where my foot fetish started.

My cousins would put me in the middle of the floor to show off my dancing skills. I was too shy to do it if there were too many people. It would scare me, and I would stay close to Tia. But if it was just a few friends, or people I was familiar with, the ham and cheese would come out and I’d take center stage, doing my little ditty.

By the age of two, I was starting to complete full sentences (most two-year-olds only use two- to three-word sentences, thank you very much!) and pointing to words and saying them out loud while the very few children’s books Tia had around—like Fun with Dick and Jane—were read to me and to the new baby Lorraine by my cousins and our babysitter—a Jewish woman and friend of Tia’s named, of all things, Rosie. Lorraine’s arrival was another telenovela tale that will come later. And speaking of telenovelas, I’d walk up to the television and point to the familiar Spanish soap opera characters, saying their names too.

I loved watching movies with Tia. She loved classic American film noir and Westerns. She told me that when I was two and three I also loved musicals and comedies. She would lie on her side, rubbing her feet together, with me lying next to her—or, my favorite position, on top of her—watching Shirley Temple or Bob Hope. I loved Bob Hope. Singing was another favorite thing we’d do together, especially the Beatles and Shirley Temple tunes (“Animal crackers in my soup, Monkeys and rabbits loop the loop …”). Tia had a horrible singing voice, but I thought she sang like a bird.

The best memory I have from that period is when I was three. It’s in bits and pieces, but Tia later filled in the parts I couldn’t remember. It was a hot Sunday in summertime, and all of the girls were out, hanging on the block with the other Puerto Rican and Hasidic kids. Tia was in the kitchen, making the early Sunday dinner, which was usually served at four o’clock. The house smelled like pollo guisado (a Puerto Rican criolla-style chicken stew made from a saucy red sofrito, a liquid blend of green peppers, garlic, onions, cilantro, culantro, and tomatoes), and it was so hot from all the pots boiling on the stove that the walls started to sweat. All the windows were open. Tia’s permed hair started to kink up. I was lying on the kitchen floor with just my diaper on, not making a peep. My behavior was disturbing her: I wasn’t sucking my thumb, like usual, and I was being strangely quiet.

Tia picked me up, took off my diaper, and washed me down in the kitchen sink with her hands. My eyes started to close from the relief of the cold water. She toweled me off and carried me into her bedroom to put on a new diaper. She went back into the kitchen, leaving the French doors open so she could still see me.

I slipped off the bed, wanting to follow her, but the room was so cool from the breeze crossing through the rooms. I stayed standing next to the edge of the bed with my head lying on top, sucking my thumb and rubbing my fingers on the little peach balls on her bedspread. My head was turned in a way so that I could still see her, over the stove, cooking. She turned to me and smiled. I was in heaven. I felt loved, safe, cool, and clean.

I felt like that most of the time in Tia’s house. Outside of my screaming fits, the only time that I had conflicted memories was when Tio Ismael would come around.

Tio Ismael, as I knew him when I was a baby, would visit the house often. Well, often enough for me to remember him. He was always in a suit and tie, or in his army jacket—always clean. He was so curious to me. I was attracted to him like a magnet was pulling my attention toward him. I always had this urge to touch his big, brutal Taino nose, his coarse, curly hair, or his bottom lip that teardropped down whenever he smiled. And he smelled good, but different. There weren’t a lot of men around our house, so the male scent was perplexing and titillating.

Tio Ismael was always happy to see me, but would cry whenever he’d pick me up, which would then make me cry. Tia was always right there to scoop me up in her arms if I began to get upset by him. After a while, I became afraid of him. He was so jumpy and stared at me all the time. When he’d come into a room, I’d run on my tiny feet to Tia, quietly grabbing at her big, cottage-cheesy thighs, screaming, “Mommie! He scares me,” with my eyes still glued to his.

• • •

Three years had passed. I was happy and loved. Then my mother reappeared, out of nowhere. Millie, who was about twelve years old at the time, answered the door. Her mouth fell to the floor.

“Doña Lydia!” she gasped. “Mommie!” she screamed as she bolted down the hallway.

She ran to Tia. The house went quiet. Tia nervously picked me up and walked over to the door.

“Hola, Lydia. Como tu tas?” Tia nervously asked with a forced, polite smile.

Tia told me that when I turned and saw my mother’s face, I immediately reached for her. Unbeknownst to me, this broke Tia’s heart, but she concealed her pain. Lydia grabbed me up in her arms.

“I came for the baby,” she said nonchalantly, with a casual smile. “Thank you for taking care of her, Minguita. I must go. I have a lot of things to do. Wave good-bye, say, ‘Bye, bye, Tia.’ ”

“Tia”? Who’s Tia? I immediately knew something was wrong. I saw Tia’s tears roll down from her eyes, and then she screamed a scream that jolted me to my core. I started screaming too. I reached back out to Tia. Tia reached for me too.

“Let’s go, Rosamarie,” my mom said as she snatched me away from Tia’s reach. “Come with Mommie.”

Mommie? She’s not my mommie—Mommie’s my mommie. Confusion flooded my head and frightened my heart. Lydia rushed with me down the hallway, while Tia and my cousins followed right behind her. At the door, my aunt fell to her knees, grasped her hands together, and pleaded.

“Ay, por favor, Lydia! Don’t take her. I beg you. Yo te’dinero! [I’ll give you money]. Algo! Algo! [Anything! Anything!] Por favor! Please! Don’t take my baby!”

“My baby!” That was the wrong thing to say to a crazy person. Lydia’s face contorted with hate, resentment, pain, guilt, and revenge. She quickly turned and was out the door, slamming it behind her. Tia screamed a scream that was heard throughout the building. She grabbed her heart, fell to her knees, and went into cardiac arrest—literally. My cousin Titi rushed to the neighbors’, banging and screaming on the door, pleading for someone to call an ambulance.

CHAPTER 3

SAINT JOSEPH’S Catholic Home for Children in Peekskill, New York, was fifty miles north of the city. “The Home” was situated on the edge of the Hudson, along the Metro-North train tracks, right up the hill from the train station. The campuslike compound, consisting partly of medieval-looking stone buildings and partly of plain cement buildings, sat on eight sparsely green, hilly acres.

I don’t remember the ride up to the Home. I don’t remember how many days had gone by since Lydia took me from Tia. I don’t even remember if I went to Lydia’s house or if she took me straight up to the Home. I just remember finding myself sitting in the “Baby Girls” playroom, seated on Lydia’s lap across from an old lady with a funny scarf on her head. She looked like those church ladies in the old black-and-white movies Tia and I used to watch. Lydia was talking to the old lady—in a calm way, negotiating a deal, but also like a victim, acting as if she didn’t want it to happen.

I started to get scared. I was fidgeting, looking around at this unfamiliar place. There were other ladies with the same thing on their heads, along with some young women dressed in regular clothes, leading other tiny kids around who were formed into lines. Some stole glances at me. A couple of men with dark robes on came in. They made me more scared than I already was. I didn’t want to be there. Lydia kept bouncing me up and down on her legs, trying to calm me. I tried to wiggle out of her arms. Then she shook me, ha

rd, and I went still. I had never been spanked, punished physically, ever. That was the first time I began to fear her wrath.

All of a sudden, we were walking into another room, with an open door that led outside. Oh, I thought, it’s all going to be over. Next thing I knew I was being handed over to the old lady with the scarf on her head as Lydia continued out the open door, waving good-bye to me, with tears streaming from her eyes. Were the tears sincere? Who knows. I started to scream, reaching my arms out to her, pleading for her to take me with her.

“Don’t you worry, Mrs. Perez, we will take good care of her. Say good-bye to your mother, Rosemary,” Sister Mary-Domenica cheerfully said.

Mother? Who is this lady? And why is everyone calling her that? She’s not my mother. Mommie’s my mother. What’s going on? My heart started racing. The door shut behind Lydia, and she was gone. In that moment, I became a ward of the state of New York and the “property” of the Catholic Church.

• • •

“Shh! Now stop that crying. It’s all right,” Sister Mary-Domenica said as she was trying to wipe my tears away. “I said now stop that. You don’t want to get a spanking, young lady, now do you?” Her tone was seemingly nice yet I detected a tinge of meanness. I stopped crying—sort of, sniffling up my snot, still looking toward that door. The younger ladies with the scarves on their heads watched what was happening with reluctant pity.

One of them reached out and took me in her arms and said, “I’ll take her, sister.” “Thank you, Sister Ann-Marie,” replied Sister Mary-Domenica.

Sister? Why are they calling each other “sister”?

“Come on, Rosemary. Let me take you to your bed,” Sister Ann-Marie said to me as she set me down on the floor. “Would you like to see where you’re going to sleep?”

Rosemary? Why was she calling me that?

Sister Ann-Marie was petite, with a hint of blond hair peeking out from her habit. Her voice was soft and high-pitched. She led me up three steps into a dormitory filled with small bunk beds, all in a row. The room was painted a kind of baby blue and was dark, as if the lights were dimmed, even though it was still midday afternoon. There were other girls in the dormitory, ranging from infants to five-year-olds. Some heads turned to take a look at the new kid. Others ignored me, as if the arrival of a new kid was routine.

Handbook for an Unpredictable Life: How I Survived Sister Renata and My Crazy Mother, and Still Came Out Smiling (with Great Hair)

Handbook for an Unpredictable Life: How I Survived Sister Renata and My Crazy Mother, and Still Came Out Smiling (with Great Hair)